Haga click aquí para leer este texto en español

Microbiology is the study of small, or microscopic, life.

This microscopic life -- mostly in the form of protozoa, bacteria, and viruses -- solved the mystery of what causes illness. In 1877 Louis Pasteur, a French biologist, discovered the connection between a rod-like type of tiny being, or microorganism, and the cattle disease splenic fever, also known as anthrax. When this tiny creature entered the cow’s body, the cow would contract anthrax. Pasteur also discovered that heating milk before its consumption killed many of these microorganisms, thus making the milk healthier and last longer. And thus the term pasteurization was born.

Good (and bad!) things come in small packages...

Microorganisms can be good or bad, depending on their composition and where they are found. We need them to digest our food, make bread rise, and brew beer, as well as break down waste. Basically they are just about everywhere -- from our skin and bodily fluids to the air we breathe and the water we drink.

The basic groups of microorganisms are worms, fungi, protozoa, bacteria, viruses and prions. When these microorganisms cause disease we call them germs. While worms and fungi can often be seen with the naked eye, protozoa, bacteria, viruses and prions can only be detected with microscopes or extremely powerful microscopes, called electron microscopes.

Bacterial Wonder

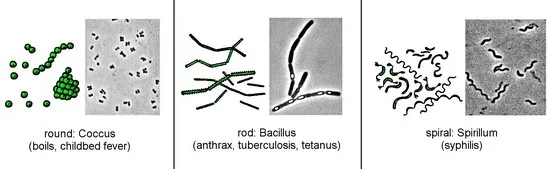

Let’s take the case of bacteria. Some bacteria are essential to the survival of life, like the nearly 500 types of bacteria that live in our intestinal tract and help us digest our food. And some bacteria we would like to do without, for example the bacteria that cause Streptococcus (strep throat), Tuberculosis, Whooping Cough, and Gonorrhea. There are thousands and thousands of bacteria, which usually range in size from 0.3-10 μm (micrometers) and are comprised of one cell. In order to survive, bacteria must eat, breathe, make waste and be able to reproduce. They are either rod-shaped, round, or spiral.

Going Viral

Viruses are even smaller than bacteria, about one-thousandth smaller! They are not comprised of cells like bacteria, but rather protein-encased genetic material like DNA or RNA. They cannot survive on their own and therefore are actually parasites, beings which must grow inside the cells of the host organism. Whereas bacteria are actual live beings and reproduce, viruses are not actually alive (think of them as messages transferred between cells) and must replicate themselves in order to proliferate. Famous examples of viruses include everything from the common flu to polio, hepatitis, rabies, HIV, SARS and Ebola.

Germ Warfare

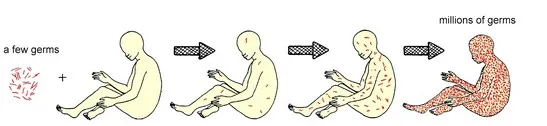

Microorganisms are not too picky about their accommodations. As long as they can find sufficient food, temperature, and moisture, they will start to multiply, and quickly! They will begin to divide themselves in the first 20 minutes, and six hours later, there will already be 65,000 of them!

It’s amazing that we don’t get sick more often considering how many types of germs are out there and how quickly they multiply inside us. When germs enter our body, our first line of defense is our skin, which tries to kill it. If that doesn’t do the job, then our immune system takes over and brings out the big guns, like macrophages, a type of white blood cell that “eats” foreign cells. But if the immune system fails (which is more likely when the body is weak), and the germ takes hold inside of our bodies, then we say the person has an infection, which may or may not be helped by drugs. Infection is often accompanied by fever and inflammation.

The Battlefronts

We say that we are contaminated when disease-causing germs enter our body and when instruments are used in an operation on a diseased person. In short, anywhere that germs live -- on a body or a thing -- is said to be contaminated. Even though, technically, instruments are not contaminated unless directly exposed to germs, nevertheless all instruments used in surgery are treated as if they are contaminated so that proper measures are taken to kill all microorganisms before the equipment is used again.

Germs are spread in the following ways:

- Direct bodily contact by touch

- Air that we breathe or particles and droplets in the air that land on our skin

- Contaminated food

- Contaminated animals and insects

- Contact with contaminated materials and equipment.

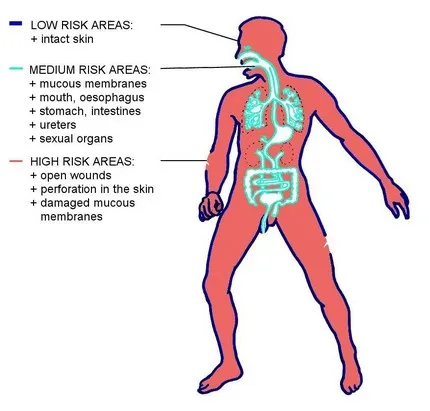

What are the body’s chances of success in fighting against germs? It depends on which battlefront the fight takes place. There are three general areas of germ entry in the body: low risk, medium risk, and high risk:

- LOW RISK: Skin. The skin is the body’s first line of defense and is able to fight off most microorganisms.

- MEDIUM RISK: Mucous Membranes. These are the special coatings found on the surfaces of many organs that are in direct contact with the outside world. The slimy fluid is called mucous and it kills many germs. We have mucous in our tears, saliva, stomach acid, and sexual organs, just to name just a few.

- HIGH RISK: Open Wounds & Sterile Organs, Tissues, and Fluids. Usually microorganisms are found on the skin, mucous membranes, in the genito-urinary system, and in the digestive tract. In all the other organs, known as the sterile organs, tissues, and fluids, there are no microorganisms. Examples of sterile fluids are blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Damaged skin and damaged mucous membranes are also in this category. Since there is no barrier to reach the body’s inner bodily fluids, germs can easily enter and have a high likelihood of causing infection.

Mighty Microorganisms Demystified

To recap, we learned that microbiology is the study of microscopic life, which includes microorganisms like bacteria and viruses. When those microorganisms cause disease, we call them germs. Under the right conditions, germs can multiply very quickly, and if they are not killed by the skin or immune system, they can cause an infection. Germs are spread through contact with contaminated food, animals, materials and equipment, as well through direct bodily contact and the air. And finally, where the germs enter our body strongly determines our chance of infection. The least risk area is our skin, followed by the medium risk area of our mucous membranes, and finally the highest risk space where germs enter our bodies via open wounds and sterile organs.

Check out our next post in this series, “Preventing the Spread of Infection in Hospitals,” to understand how we kill germs. We will explore the important concepts of cleaning, disinfection, and of course, STERILIZATION!

Comments and questions are welcome, as always, in the comment section below.

(Post based on Sterilization of Medical Supplies by Steam by Jan Huys. Except for photo of Louis Pasteur, all images appear with permission from Huys.)