No Reason to Panic?

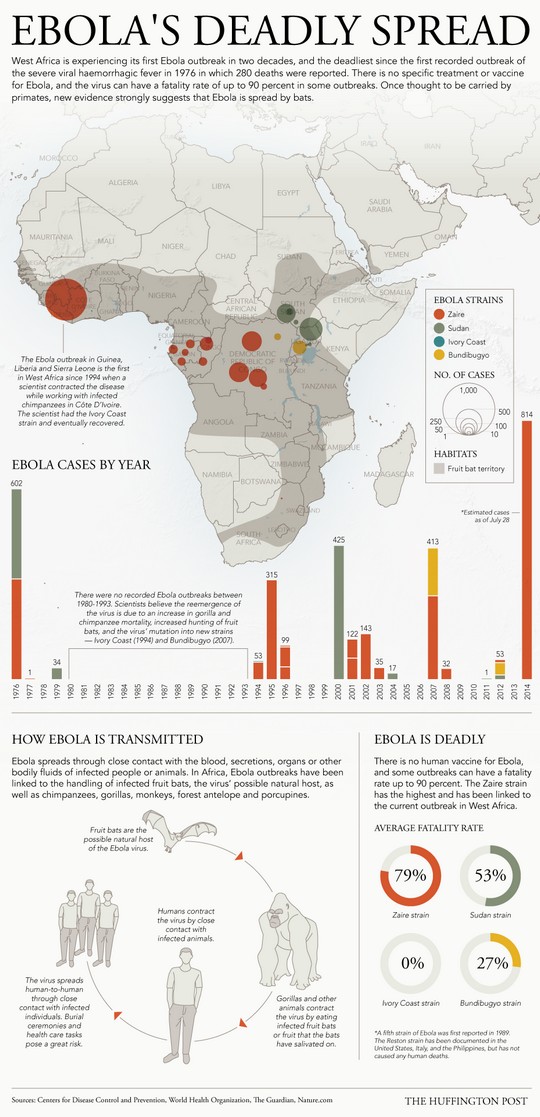

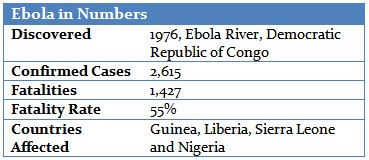

The Ebola outbreak began in Guinea in March 2014, spreading to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and – in the last few weeks –Nigeria. Over 2,615 people have been infected, with more than over 1,427 dead as of August 25 – that’s a mortality rate of over 55%. This is the deadliest outbreak of the virus since its discovery in 1976. Many health care professionals say there’s no reason to panic, but on August 8, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency.

This post demystifies Ebola, providing basic facts and explaining the role of infection control.

Ebola and the Global Village

Thanks to crowd wisdom and online technology, organizations such as the WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) track and document deadly diseases faster and better than ever. Scanning social networks, blogs, and other online media, these agencies have collected reports and discussions about Ebola cases, using these and other data to create a live, interactive, and highly accurate map of the epidemic. Such tracking of a contagious disease in real time helps control its spread worldwide.

Not the Best of Families

Ebola virus disease (EVD), formerly Ebola hemorrhagic fever, broke out in 1976 in Nzara, Sudan, and in a village near the Ebola River in Congo. Ebola ranks among the long, stringlike members of the Filoviridae family – from the Latin filo, thread – and can cause severe hemorrhagic fever in humans and primates. Four species have been identified: Ivory Coast, Sudan, Zaire, and Reston. Zaire, the deadliest, is now spreading.

Who's Got It?

Ebola is most likely transmitted by exposure to infected primates. Fruit bats also carry the disease and may be its natural hosts.

The first symptoms are flu-like: fever, muscle pain, weakness, headaches, and sore throat. Next comes vomiting, diarrhea, rash, and possibly liver and kidney malfunction. The final, usually fatal phase can involve severe internal and external bleeding and multiple organ failure.

Human Transmission and Infection Control

Ebola is transmitted by contact with infected bodily fluids. (Caregivers often catch it when cleaning up vomit or diarrhea.) It enters the body through the nose and mouth. Incubation lasts two to twenty-one days, during which patients become contagious only once they show symptoms. This is why simple infection control measures can save lives and contain the disease.

Ebola is not transmitted through the air, which makes it slightly easier to control. At room temperature, however, it can survive outside its host for days. That’s another reason infection control is vital. With adequate sterilization of equipment and availability of disinfectants, proper cleaning of infected environments, and effective quarantining, the virus can never gain a foothold.

Sterilization and infection control are particularly important in the health care environment, lest health care providers themselves become infected, tragically spreading the very plague they sought to stop.

According to the CDC, Ebola research must take place in a biosafety level 4 lab, reserved for the deadliest diseases.

Is Ebola a Global Threat?

Does Ebola threaten the Western world? Although several health care workers infected in Africa were shipped to the U.S. and Europe for treatment, Ebola hasn’t spread to the West. Experts say it won’t, simply because Western hospitals’ infection control standards are much higher than those elsewhere.

Ethics and Education

The WHO recently endorsed the use of experimental drugs to combat Ebola in West Africa. While there’s no known cure, three such medicines offer hope. Is it ethical to administer an untested drug with unknown side effects? This is what Doctors Without Borders has called the “impossible dilemma.” Is it ethical to administer an untested drug with unknown side effects?

Aside from merely manufacturing sterilization and infection control equipment, we at Tuttnauer seek to educate. The more our customers understand infection control, the more effectively they’ll use our autoclaves. Thus, in developing regions such as Africa, Tuttnauer provides training. Beyond the technicalities of autoclave usage, maintenance, and repair, we focus on the theory and practice of infection control, professionalizing our clientele. It’s all part of our modest contribution to infection control.